9 - De-identify sensitive data

Scenario: Can you show the steps taken and measures put in place to avoid data breaches? Is your data identifiable?

Data is considered sensitive when it can be used to identify an individual, species, object, or location that introduces a risk of discrimination, harm, or unwanted attention.

Categories of sensitive data include:

- personal data

- health and medical data

- ecological data that may place vulnerable species at risk

- culturally sensitive data

Separating or de-identifying your data usually occurs to protect an individuals privacy. According to the Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988, “personal information is de-identified if the information is no longer about an identifiable individual or an individual who is reasonably identifiable”.

De-identified information is no longer considered personal information and can be shared. More information on legal definitions and requirements on privacy can be found in the Commonwealth Privacy Act.

De-identifiying aims to allow data to be used by others for publishing, sharing and reuse without the possibility of individuals/location being re-identified. It may also be used to protect the location of archaeological findings, culturally sensitive data (for example archaelogical sites at risk of vandalism or looting) or the location of endangered species.

Any identifiers (name, date of birth, address or geospatial locations etc.) should be removed from main data set and replaced with a code/key. The code/key is then encrypted and stored separately. By storing de-identified data in a secure solution, you are meeting safety, controlled, ethical, privacy and funding agency requirements.

Re-identifing an individual can be possible by recombining the de-identifiable data set and the identifiers. There are processes that can be undertaken to mitigate this.

What is de-identification?

The term ‘de-identification’ carries many meanings, including reference to the process of removing or altering information e.g. deleting information that explicitly makes any person identifiable by such information such as names or date of birth. It can also mean altering data to a point where no person can be ‘reasonably identified’ from the information. That is, when a person is distinguished from a group by means of establishing a link between available information and a specific individual. (OAIC, 2017)

What can happen if data is de-identified in one source, but can still reasonably identify individuals?

Case study one: During a research project conducted by a university student in 2000, information detailing Massachusetts public servants health insurance information was obtained vua public means. The dataset had names, addresses, social security numbers and other ‘identifying’ information removed. The researchers then obtained a dataset detailing the state voter enrolments for the capital city of Cambridge. This dataset contained personally identifiable information such as name, postcode, address, sex, and date of birth for every enrolled person. Comparing the two datasets, it was reasonably easy to notice six people in the city of Cambridge were born on the same data as the State Governor, with half being men. The voter data allowed researchers to pinpoint the Governor as the only on of those persons living in a certain Cambridge postcode. Once again comparing the voter data to health data, a significant amount of the Governor’s health information was revealed. Including medical diagnoses and prescriptions. (Ohm, 2010 and OAIC, 2017)

Scenario: Can you show the steps taken and measures that should have been put in place to avoid such a data breache? Is your data identifiable?

Why de-identify?

There are a number of reasons that you will need to de-identify data, usually all these will apply to some extent (OVIC, 2022):

- When required by law such as the Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 which will be discussed later on in this chapter.

- For risk management purposes such as using a de-identified dataset rather than a complete original to minimise risk of a privacy breach.

- To promote transparency and accountability by de-identifying data you can increase open access, and auditing where necessary.

- To enable information to be used in innovative ways such as supply de-identified data to collaborators or other research teams, or to assist policy and/or decision making.

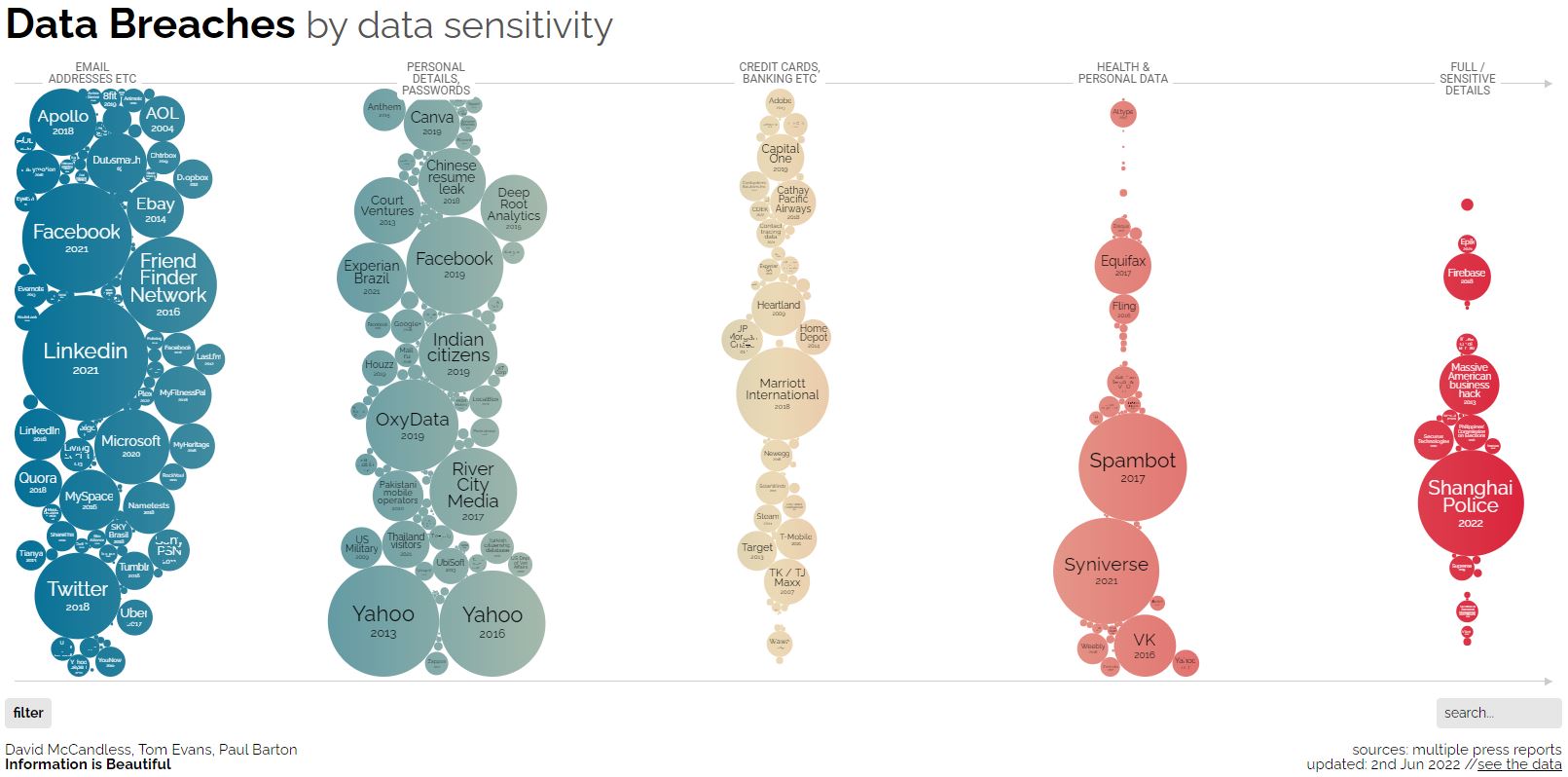

Ultimately, de-identifying data is an effective mechanism to make sure you do NOT appear on this chart:

Australian practical guidance for de-identification

-

The ARDC’s Identifiable Data resource collates a selection of Australian and international practical guidelines and resources on how to de-identify datasets. In addition, their Publishing sensitive data guide is intended for researchers who own a data set and wish to share safely with fellow researchers or for publishing of data.

-

The Australian Government’s Office of the Australian Information Commissioner (OAIC) and CSIRO Data61 have released a ‘De-identification Decision Making Framework’ which is a “practical guide to de-identification, focussing on operational advice”. The guide will assist organisations that handle personal information to de-identify their data effectively.

-

The OAIC also provides high-level guidance on de-identification of data and information, outlining what de-identification is, and how it can be achieved.

-

The Australian Government’s guide to health privacy, includes techniques for making a data set non-identifiable and example case studies.

-

Office of the Information Commissioner Queensland has developed excellent guidance on Privacy and De-identified data.

Tips for managing de-identification

- Plan de-identification early in the research as part of your data management planning

- Retain original unedited versions of data for use within the research team and for preservation

- Create a de-identification log of all replacements, aggregations or removals made

- Store the log separately from the de-identified data files

- Identify replacements in text in a meaningful way, e.g. in transcribed interviews indicate replaced text with [brackets] or use XML markup tags e.g.

.....

Quantitative de-identification methods

Some research may require the use of de-deidentification methods that produce a quantitative measure of how de-identified the data is, and thus whether or not it is suitable for continued use.

k-Anonymity

k-anonymity was introduced in the late 1990’s and is built on the concept that individually identifiable data can be combined across rows with similiar attributes. It is often referred to as hiding in the crowd. The k refers to the number of times a combination of variables appears in a dataset. The smaller (closest to 0), the better. (Devane, 2021)

An example of this in practice is to imagine a dataset of 1000 individual records specifying information such as name, postcode, age, gender, body measurements, and key health diagnosis data. In order to achieve k-anonymity in this instance, names could be removed as they are not necessary to analyse health data. Postcodes can be extended to include a local government area, council municipality or other geographic region. Furthermore, age could be generalised to ranges such as 18-24, 25-40 and so on. (Devane, 2021 and OVIC, 2022)

Lets say we have removed data and generalised remaining variables to a point that only 2 combinations of age bracket, geographic area, and gender appear throughout the dataset at any one time. It would then be said that the dataset has a k-anonymity of k = 2 or is 2-anonymous. (Devane, 2021)

Differential privacy

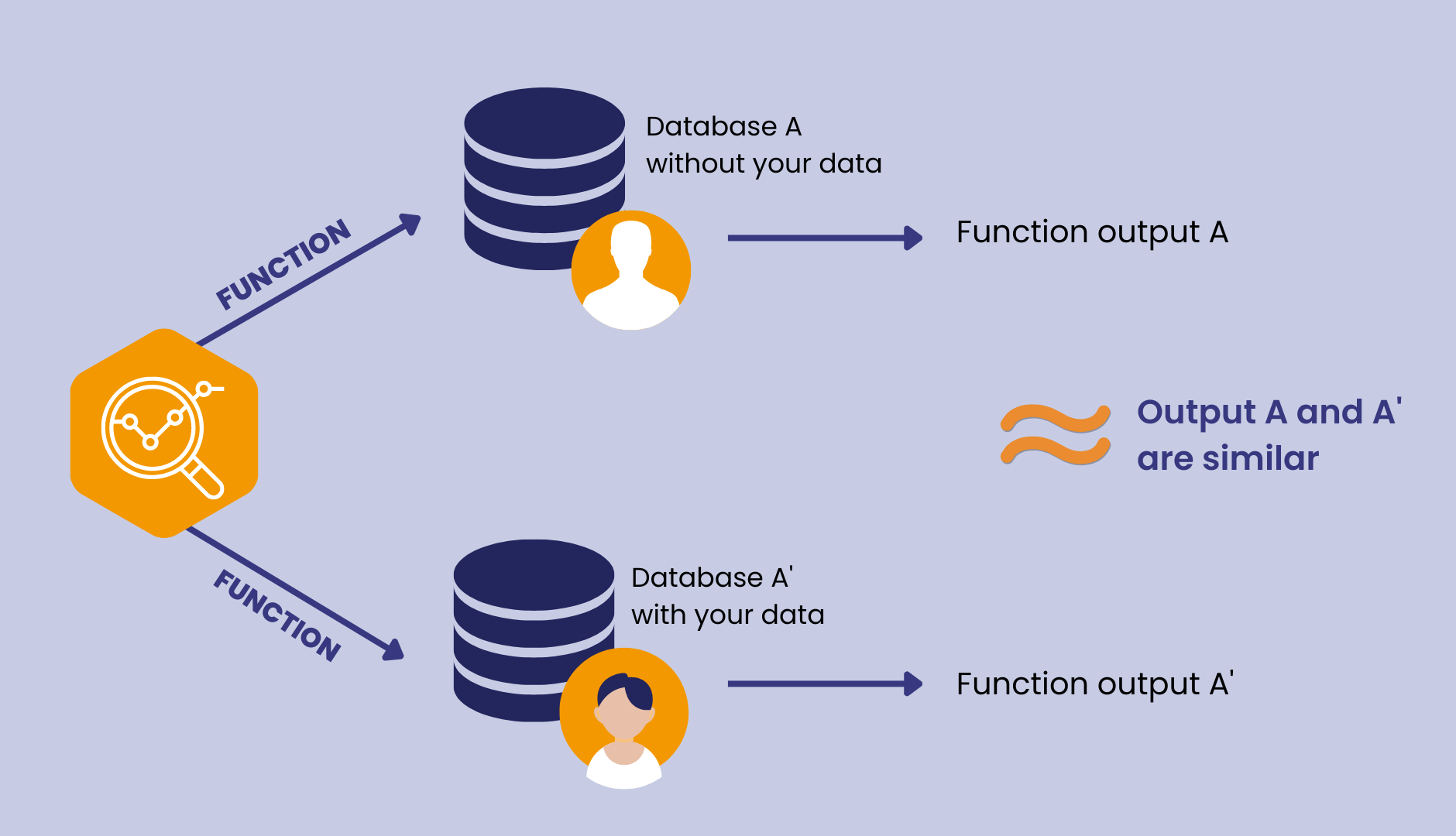

Differential privacy is a method primarily reserved for large databases, through which the use of these databases is to derive a statistical output.

The Harvard University Privacy Tools Project (2023) defines differential privacy as:

“…a rigorous mathematical definition of privacy. In the simplest setting, consider an algorithm that analyzes a dataset and computes statistics about it (such as the data’s mean, variance, median, mode, etc.). Such an algorithm is said to be differentially private if by looking at the output, one cannot tell whether any individual’s data was included in the original dataset or not. In other words, the guarantee of a differentially private algorithm is that its behavior hardly changes when a single individual joins or leaves the dataset – anything the algorithm might output on a database containing some individual’s information is almost as likely to have come from a database without that individual’s information.”

Differential privacy works primarily through the addition of calibrated noise. The ‘noise’ or ‘randomness’ is added to the dataset in a mathematically sound way that preserves overall accuracy of analysis.

An example of this in practice is if a researcher administers a survey exploring how many individuals have cheated on tax returns in the previous financial year as a ‘yes or no’ response. Participants are told that all responses will undergo a differential privacy process to encourage truthful responses. In this scenario, an individual answers the question and then a coin is tossed. If the result is heads then the response is kept as is and recorded correctly. If the result is tails, the coin is tossed a second time. Again, if the result is heads then the response is kept as is otherwise the opposite answer is recorded.

In the above example, there is a 75% chance that the correct answer will be recorded, but ultimately it gives the respondent a degree of plausibile deniability if questioned or attempted to be held liable. This high percentage of a correct answer maintains consistency in data collection and allows for patterns to still be inferred.

There are some limitations to differential privacy which make it more of a unique tool rather than one that should be used all the time. These limitations include but are not limited to (Harness, 2022):

- Suitability only for large datasets

- Results are not exact for general computations

- Results are not suitable for individual or microscale insights

Watch the short video below from USA National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) to learn how differential privacy works.

Management of identifiable data

Data may often need to be identifiable during the process of research. If data is identifiable then ethical and privacy requirements can be met through access control and data security. This may take the form of:

- Control of access through physical or digital means (e.g. passwords)

- Encryption of data, particularly if it is being moved between locations

- Ensuring data is not stored in an identifiable and unencrypted format when on easily lost items such as USB keys, laptops and external hard drives.

- Taking reasonable actions to prevent the inadvertent disclosure, release or loss of sensitive personal information. Source: ARDC

Five Safes framework: Working with sensitive data

The Five Safes framework is an approach to assessing and managing risks associated with sensitive data sharing and release. It has been adopted by Australia’s major statistics agencies including the Australian Bureau of Statistics and Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Applying the framework to the data, its users and their purpose, storage and eventual research outcomes, enables researchers to access their large, linked datasets for valid research purposes.

Five Safe Framework has five dimensions with associated risks and management solutions:

- safe people

- safe projects

- safe settings

- safe data

- safe outputs

Watch this short video from the UK Data Service on how the framework can be applied.

QCIF Bioinformatics is a service available to Griffith University researchers via the University’s membership with QCIF.

Consultations are free and capped at one-hour, however they can be highly beneficial to a variety of research tasks, including:

- Experiemental design (e.g. sample size, and power calculations)

- Statistical/Bioinformatics analysis methods

- Data Management Planning

Contact Griffith University’s eResearch team to access the service.